Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) is a complex and chronic medical condition characterized by the body’s inability to produce insulin. It differs from Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) in its etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment modalities. This article aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of T1D in medical terms, including its epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and complications.

Epidemiology of Type 1 Diabetes

T1D is one of the most common chronic diseases in children and adolescents, although it can occur at any age. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), approximately 1 in every 500 children and adolescents worldwide develops T1D each year. The incidence of T1D varies globally, with higher rates reported in developed countries such as Finland, Sweden, and the United States.

Etiology of Type 1 Diabetes

The exact cause of T1D is not fully understood, but it is believed to involve a combination of genetic, environmental, and immunological factors. Genetic predisposition plays a significant role in T1D susceptibility, with certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes, such as HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR4, being strongly associated with the development of the disease.

Environmental factors, such as viral infections and dietary factors, may trigger the autoimmune response leading to T1D in genetically susceptible individuals. Viral infections, particularly enteroviruses, have been implicated in the initiation of the autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells. Additionally, early exposure to cow’s milk protein and vitamin D deficiency have been suggested as potential environmental triggers for T1D.

Pathophysiology of Type 1 Diabetes

T1D is characterized by the destruction of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, leading to an absolute deficiency of insulin. The destruction of beta cells is mediated by an autoimmune process, whereby the body’s immune system mistakenly identifies beta cells as foreign and attacks them.

Autoimmune destruction of beta cells involves a complex interplay of various immune cells, including T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes infiltrate the pancreatic islets and release pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which contribute to beta cell destruction.

In addition to the autoimmune destruction of beta cells, T1D is also characterized by the presence of autoantibodies against pancreatic islet antigens, such as insulin, glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), and insulinoma-associated antigen-2 (IA-2). These autoantibodies serve as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prediction of T1D.

Clinical Manifestations of Type 1 Diabetes

The clinical manifestations of T1D are primarily related to hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) and insulin deficiency. Common symptoms include polyuria (excessive urination), polydipsia (excessive thirst), polyphagia (excessive hunger), unexplained weight loss, fatigue, blurred vision, and recurrent infections.

In severe cases, untreated T1D can lead to diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a life-threatening complication characterized by hyperglycemia, ketosis, metabolic acidosis, and dehydration. DKA requires immediate medical intervention and can result in coma and death if left untreated.

Diagnosis of Type 1 Diabetes

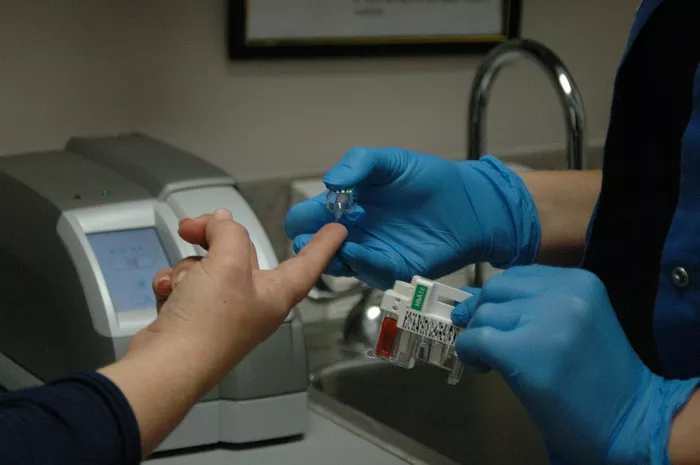

The diagnosis of T1D is based on clinical presentation, laboratory tests, and the presence of autoantibodies against pancreatic islet antigens. Laboratory tests commonly used in the diagnosis of T1D include fasting blood glucose levels, oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels.

In addition to these tests, the presence of autoantibodies against pancreatic islet antigens, such as anti-insulin antibodies, anti-GAD antibodies, and anti-IA-2 antibodies, supports the diagnosis of T1D. Measurement of these autoantibodies can help differentiate T1D from other forms of diabetes, such as T2D.

Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes

The mainstay of treatment for T1D is insulin therapy, which aims to replace the deficient insulin and regulate blood glucose levels. Insulin therapy is typically administered via subcutaneous injections or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (insulin pump therapy).

Several types of insulin are available for the management of T1D, including rapid-acting insulin analogs (e.g., insulin lispro, insulin aspart), short-acting insulin (regular insulin), intermediate-acting insulin (NPH insulin), and long-acting insulin analogs (e.g., insulin glargine, insulin detemir). The choice of insulin regimen depends on individual patient factors, including lifestyle, preferences, and glycemic control goals.

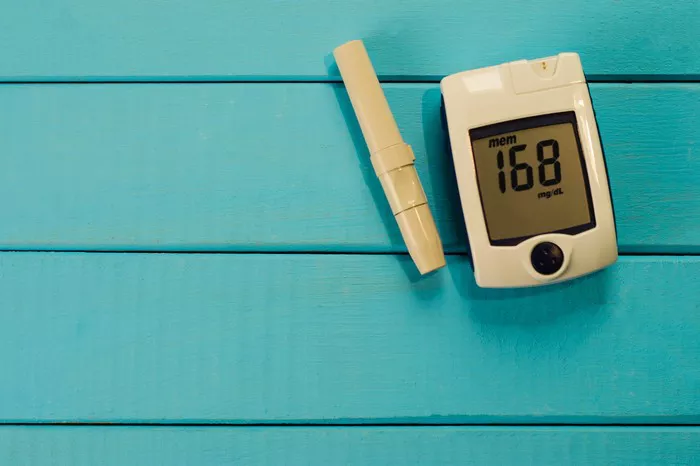

In addition to insulin therapy, comprehensive management of T1D involves dietary modifications, regular physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, and education on diabetes self-management. Carbohydrate counting, insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios, and correction factors are important tools for optimizing insulin dosing and blood glucose control.

Complications of Type 1 Diabetes

Despite advances in diabetes management, T1D remains associated with an increased risk of acute and chronic complications. Acute complications of T1D include hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), both of which require prompt medical attention.

Chronic complications of T1D result from long-term exposure to hyperglycemia and include microvascular complications (e.g., diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, diabetic neuropathy) and macrovascular complications (e.g., cardiovascular disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease). Tight glycemic control, blood pressure management, lipid-lowering therapy, and regular screening for complications are essential for reducing the risk of long-term complications in patients with T1D.

Conclusion

In conclusion, T1D is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by the destruction of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, leading to insulin deficiency and hyperglycemia. Although the exact cause of T1D remains unclear, genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and immunological mechanisms are believed to play key roles in its development.

The diagnosis of T1D is based on clinical presentation, laboratory tests, and the presence of autoantibodies against pancreatic islet antigens. Treatment involves insulin therapy, dietary modifications, regular physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, and education on diabetes self-management.

Despite advances in diabetes management, T1D remains associated with an increased risk of acute and chronic complications. Comprehensive management strategies aimed at achieving and maintaining glycemic control are essential for reducing the risk of complications and improving the long-term outcomes of patients with T1D.