Diabetes mellitus, a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by elevated blood glucose levels, encompasses a diverse spectrum of conditions with varying etiologies, pathophysiological mechanisms, and clinical presentations. From the classic distinction between type 1 and type 2 diabetes to the less common types such as gestational diabetes and monogenic forms, understanding the nuances of each subtype is essential for accurate diagnosis, personalized management, and prevention of complications. This article aims to elucidate the intricacies of the four different types of diabetes, shedding light on their epidemiology, risk factors, diagnostic criteria, management strategies, and potential complications.

1. Type 1 Diabetes: Unveiling the Autoimmune Cascade

Type 1 diabetes, previously known as insulin-dependent or juvenile-onset diabetes, results from autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells, leading to absolute insulin deficiency. The autoimmune process typically begins in genetically susceptible individuals, triggered by environmental factors such as viral infections, dietary antigens, or other immune insults. As beta cell mass declines, insulin secretion diminishes, resulting in hyperglycemia and metabolic derangements.

Epidemiology and Incidence: Type 1 diabetes accounts for approximately 5-10% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes worldwide, with the highest incidence observed in children, adolescents, and young adults. While traditionally considered a pediatric condition, type 1 diabetes can occur at any age, with a second peak in incidence observed in individuals over 30 years old.

Clinical Presentation: The onset of type 1 diabetes is often abrupt, characterized by classic symptoms such as polyuria (excessive urination), polydipsia (excessive thirst), polyphagia (excessive hunger), unexplained weight loss, fatigue, and blurred vision. Individuals with type 1 diabetes are prone to developing diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a life-threatening complication characterized by hyperglycemia, ketosis, and metabolic acidosis.

Risk Factors and Etiology: Genetic predisposition, particularly certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles, plays a significant role in susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Environmental factors, such as viral infections (e.g., enteroviruses, Coxsackie viruses), dietary antigens (e.g., cow’s milk proteins), and early childhood exposures, may trigger or accelerate the autoimmune destruction of beta cells in genetically susceptible individuals.

Diagnostic Criteria and Management: The diagnosis of type 1 diabetes is based on clinical symptoms, blood glucose levels, and the presence of autoimmune markers, such as islet cell antibodies (ICA), glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies (GADA), insulin autoantibodies (IAA), and zinc transporter 8 antibodies (ZnT8A). Treatment revolves around exogenous insulin replacement therapy to restore physiological insulin levels and maintain optimal glycemic control.

2. Type 2 Diabetes: Unraveling the Complex Interplay

Type 2 diabetes, formerly known as non-insulin-dependent or adult-onset diabetes, is characterized by insulin resistance, impaired insulin secretion, and progressive beta cell dysfunction. Unlike type 1 diabetes, which primarily involves autoimmune destruction of beta cells, type 2 diabetes is multifactorial in etiology, with genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors contributing to its pathogenesis.

Epidemiology and Incidence: Type 2 diabetes accounts for the majority of diabetes cases worldwide, representing approximately 90-95% of all diagnosed cases. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is escalating globally, driven by the obesity epidemic, sedentary lifestyles, unhealthy dietary habits, and aging populations.

Clinical Presentation: The clinical presentation of type 2 diabetes varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic hyperglycemia to classic symptoms of polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss. Many individuals with type 2 diabetes remain undiagnosed for years due to the insidious onset of symptoms and the absence of overt complications.

Risk Factors and Etiology: Type 2 diabetes has a strong genetic component, with certain genetic variants predisposing individuals to insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction. Environmental factors, such as obesity, sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy dietary patterns (e.g., high sugar, high fat, low fiber), metabolic syndrome, and certain ethnicities, contribute substantially to the development and progression of type 2 diabetes.

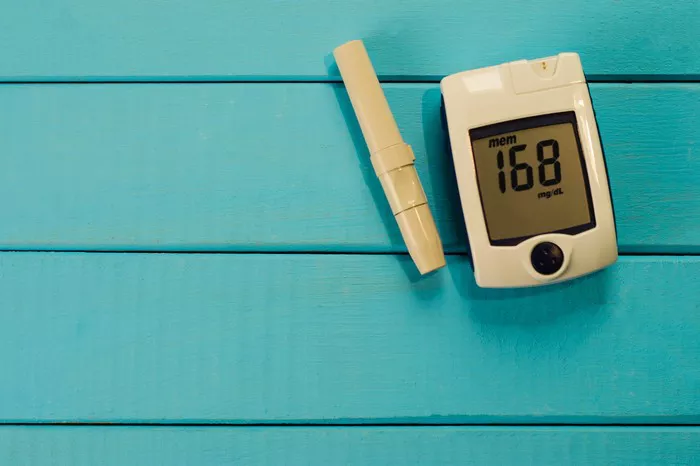

Diagnostic Criteria and Management: The diagnosis of type 2 diabetes is based on fasting plasma glucose (FPG), oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, or random plasma glucose levels in the presence of classic symptoms. Management strategies for type 2 diabetes encompass lifestyle modifications, including dietary changes, regular physical activity, weight management, smoking cessation, and pharmacotherapy.

3. Gestational Diabetes: Navigating Pregnancy-Induced Metabolic Challenges

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a form of diabetes that develops during pregnancy, typically in the second or third trimester, and resolves after childbirth. GDM arises due to hormonal changes, insulin resistance, and impaired pancreatic beta cell function during pregnancy, leading to elevated blood glucose levels and maternal-fetal metabolic alterations.

Epidemiology and Incidence: Gestational diabetes affects approximately 2-10% of pregnancies worldwide, with variations in prevalence depending on population demographics, screening practices, and diagnostic criteria. Certain risk factors, such as maternal age, obesity, family history of diabetes, previous history of GDM, and certain ethnicities, increase the likelihood of developing GDM.

Clinical Presentation: Gestational diabetes is often asymptomatic and diagnosed through routine screening during pregnancy. However, some women may experience symptoms such as increased thirst, frequent urination, fatigue, and blurred vision. GDM poses risks to both maternal and fetal health, including macrosomia (large birth weight), birth trauma, neonatal hypoglycemia, and long-term metabolic consequences.

Risk Factors and Etiology: Risk factors for gestational diabetes include maternal age over 25 years, obesity, family history of diabetes, previous history of GDM, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and certain ethnicities (e.g., Hispanic, African American, Asian, Native American). Hormonal changes during pregnancy, including increased levels of placental hormones (e.g., human placental lactogen, progesterone), contribute to insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism.

Diagnostic Criteria and Management: Screening for gestational diabetes is typically performed between 24 to 28 weeks of gestation using an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) or other validated screening tests. Management strategies for GDM focus on lifestyle modifications, including dietary counseling, regular physical activity, and glucose monitoring. Insulin therapy or oral antidiabetic medications may be initiated if glycemic targets are not achieved through lifestyle interventions alone.

4. Monogenic Diabetes: Unraveling Genetic Variants

Monogenic forms of diabetes, also known as maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) and neonatal diabetes mellitus (NDM), are rare genetic disorders characterized by mutations in specific genes involved in pancreatic beta cell function, insulin secretion, or insulin action. Unlike type 1 and type 2 diabetes, which are multifactorial in etiology, monogenic diabetes results from single gene defects inherited in an autosomal dominant or recessive manner.

Epidemiology and Incidence: Monogenic diabetes accounts for a small proportion of all diagnosed cases of diabetes, estimated to be less than 2% of individuals with diabetes. MODY is more prevalent than NDM, with varying incidence rates depending on population demographics and genetic predisposition.

Clinical Presentation: Monogenic diabetes often manifests at a younger age compared to type 2 diabetes, with onset typically occurring in childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood. The clinical presentation varies depending on the specific genetic defect but may include mild hyperglycemia, nonketotic diabetes, or neonatal diabetes with severe hyperglycemia.

Risk Factors and Etiology: Monogenic diabetes is caused by mutations in genes encoding proteins involved in pancreatic beta cell development, insulin secretion, or insulin action. Family history of diabetes, early age of onset, absence of autoimmune markers, and stable glycemic control without insulin therapy are suggestive of monogenic diabetes and warrant further genetic testing.

Diagnostic Criteria and Management: Diagnosis of monogenic diabetes is based on clinical presentation, family history, biochemical markers, and genetic testing to identify specific gene mutations. Management strategies for monogenic diabetes vary depending on the underlying genetic defect but may involve lifestyle modifications, oral antidiabetic medications, or insulin therapy tailored to individual patient needs.

Conclusion: Embracing Diversity in Diabetes

In conclusion, the landscape of diabetes encompasses four distinct types, each with its unique etiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management considerations. From type 1 diabetes driven by autoimmune destruction of beta cells to type 2 diabetes characterized by insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction, gestational diabetes influenced by pregnancy-induced hormonal changes, and monogenic diabetes arising from genetic variants, understanding the diverse spectrum of diabetes is paramount for effective diagnosis, management, and prevention of complications. Healthcare providers should adopt a personalized approach to diabetes care, taking into account individual patient characteristics, risk factors, and treatment goals. With ongoing advancements in research, genetics, and personalized medicine, the future holds promise for improved outcomes and tailored interventions to address the multifaceted challenges posed by diabetes mellitus.